Using Trace Data to Find Evidence of Curiosity in Learning

Telemetry Data from IFN619 2023

Presentation on Week 13

The contents in this section were presented in classes on Week 13. The original contents were migrated from the Google Sites. For any updates after the presentation, please go to the next section.

Purpose

This was initially a short presentation to the IFN619 class - Semester 1, 2023. The initial purpose of this project page is to inform the students who opted in to provide their Jupyter telemetry data from the IFN619 class.

If you are a participant of this project, please contact me if you want to know more about this project. I will keep updating this project page as I dig more into the telemetry data.

A little recap

-

Video & participant information sheet on Canvas (see screenshot)

-

My PhD topic is about identifying and supporting curiosity in learning with a data-driven approach.

-

Telemetry data from JupyterLab environment is collected. All the data are anonymous.

-

My hypothesis: students behave differently; different patterns will correlate with features signifying curiosity.

What did I propose to do? (More information on the participant information sheet)

During the semester:

- Collect and analyse telemetry data only from the studio notebooks

- Data for students from my tutorial sessions are excluded

- Analyses only focus on class level (mainly exploratory analysis - focusing on observing patterns)

- Present a brief overview at the end of the semester (this presentation)

After the final grade is released:

- Analyse all the data from the participants

- Insights will be used as the first phase of my PhD project

Data Overview

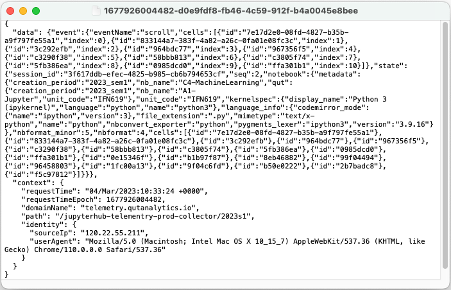

What does the original data look like?

An overview of the studio notebook data

-

Data from 96 out of 98 students (2 students never opened any studio notebooks?)

-

Some students were using their local machines. Those students might only use the Jupyter environment to sync notebooks.

-

Wide range of activities by students. Do they have different patterns of using those studio notebooks?

-

Most of the events from the top 6 are reflected in the common use of notebooks for general exploration.

-

There is a high rate of errors. What could be the potential reasons? Are these errors from a few students or all students? What types of errors are common, and are there any variations in the types of errors among students?

-

There are not many “add cell” events. Is this because students do not need to add new cells for studio notebooks? Who added cells and when did they do so?

-

It would be interesting to investigate copy/cut/paste activities. Did these activities occur only among some students? Where did they copy and paste the code from?

Now looking into events for each student…

-

Running into errors is quite common for most students.

-

It might be able to provide more insights if I standardise each student’s activities on the same scale (by looking at the proportion of each event). See below…

-

The behavioural patterns might differ depending on whether the notebook is a solution or not. This needs to be examined at the individual level.

After normalising the events…

-

A few students’ activity patterns seemed to be different, for example, #185, #190, #188, and #181.

-

It might also be because they didn’t use the Jupyter environment as their main platform.

-

This needs to be investigated at the individual level to find out.

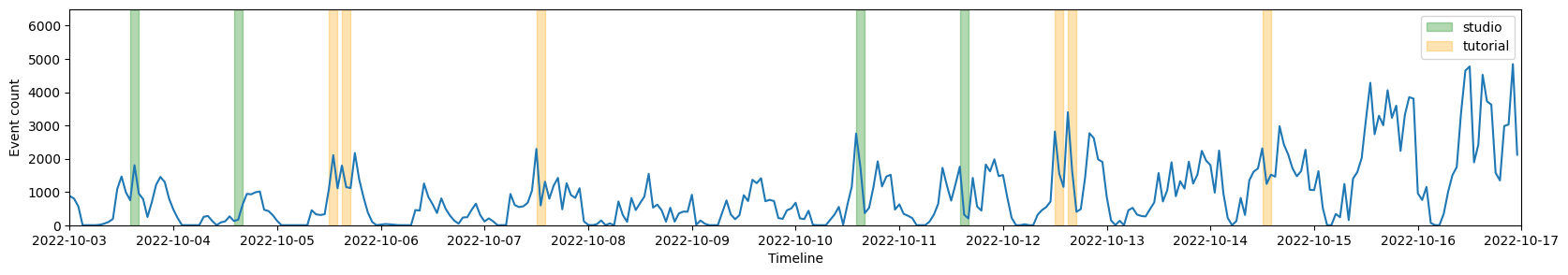

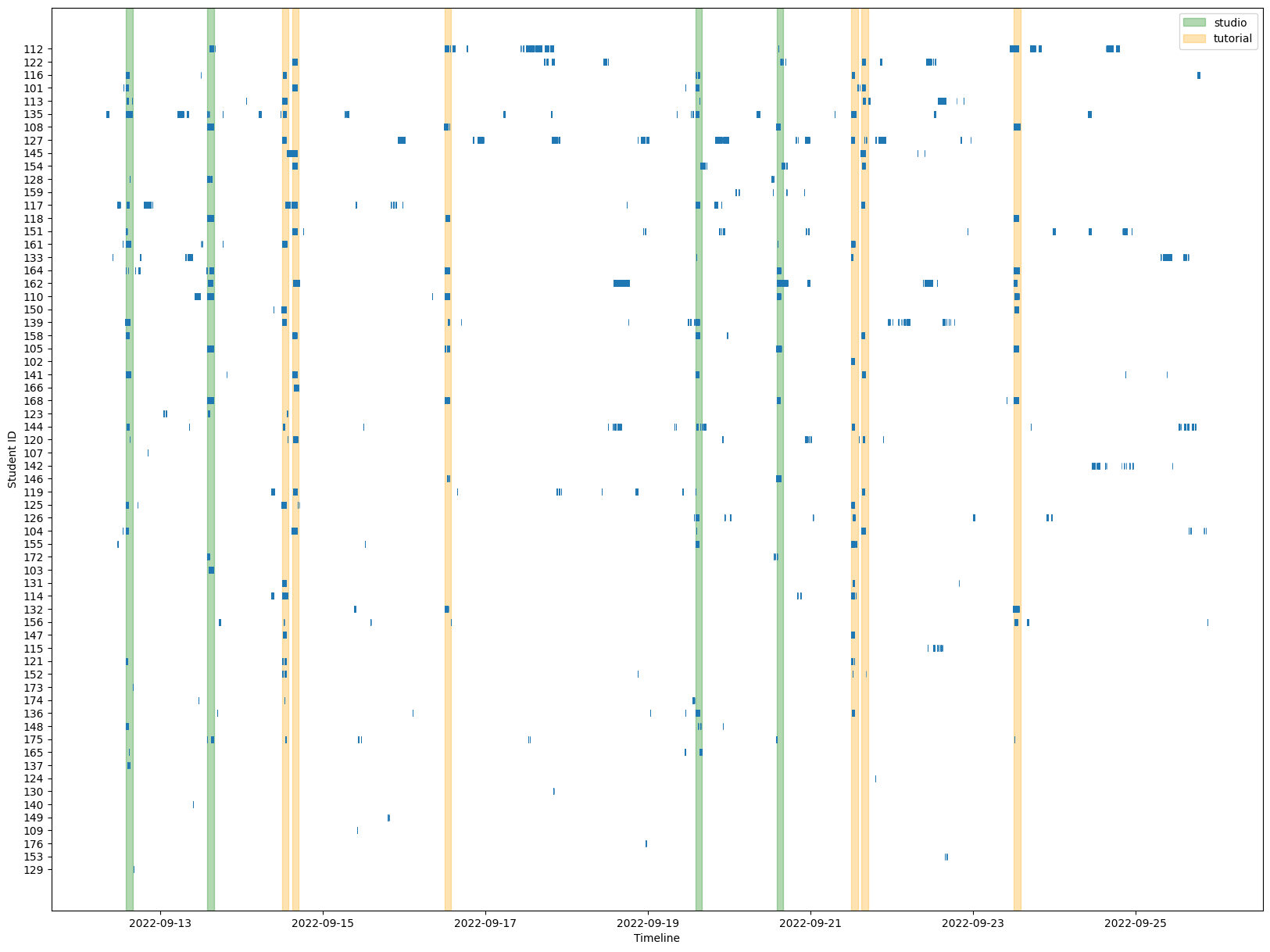

Time Series Data Visualisation - activity frequency on studio notebooks

-

Studio notebooks were mostly used during studio sessions (Duh!), and then during tutorial sessions.

-

Did student interaction decrease as the semester progressed?

-

What activities did students engage in outside of class times? Did they use that time to catch up on content or copy code for assignments?

What else do I intend to do with studio notebook data?

-

Zoom in on the studio sessions and compare them with lecture recordings.

-

Identify patterns in student interaction during class and determine when students were most interactive.

-

Analyse the data to identify curious behavioural patterns and establish connections between different patterns.

Next Steps

More analysis will be done after the semester ends…

Some explorations were mentioned earlier, such as looking into errors.

More ideas from my pilot analysis…

Analysing all the data to see when students were more active

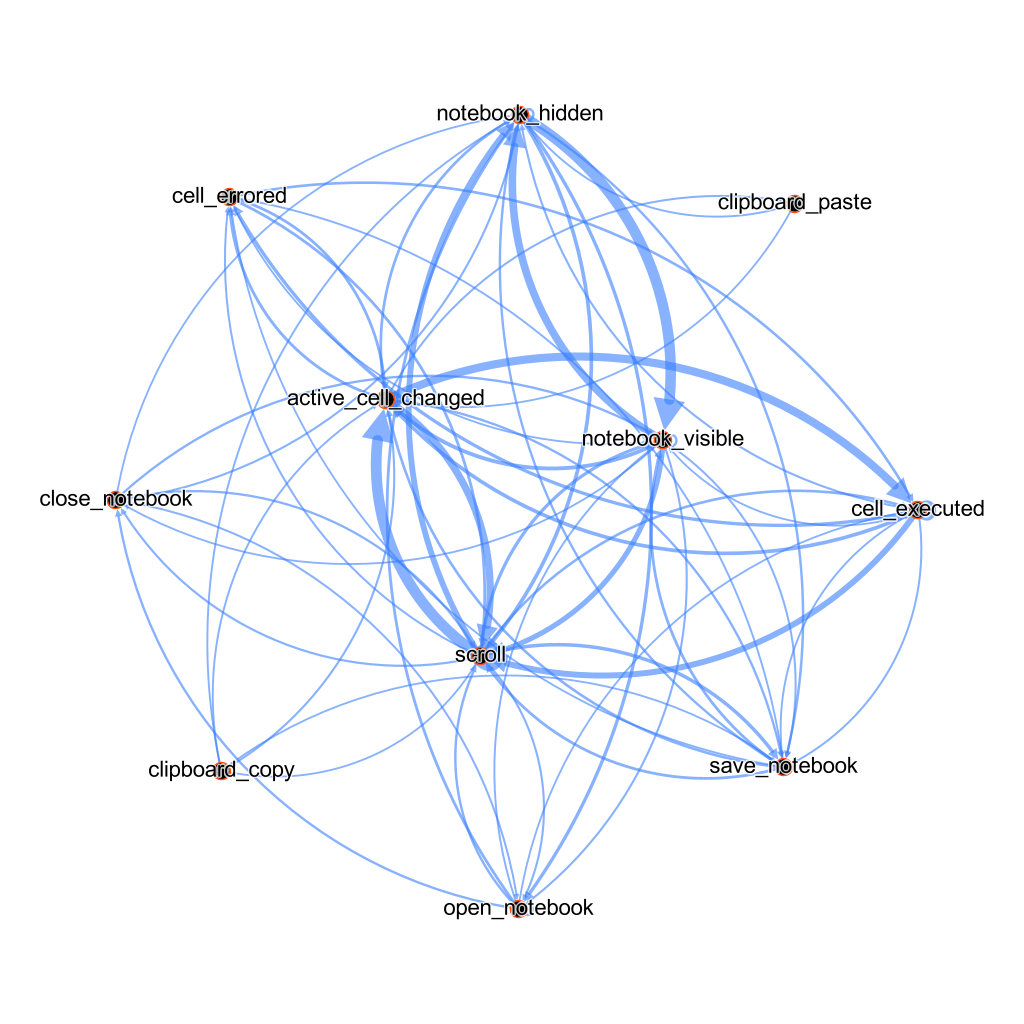

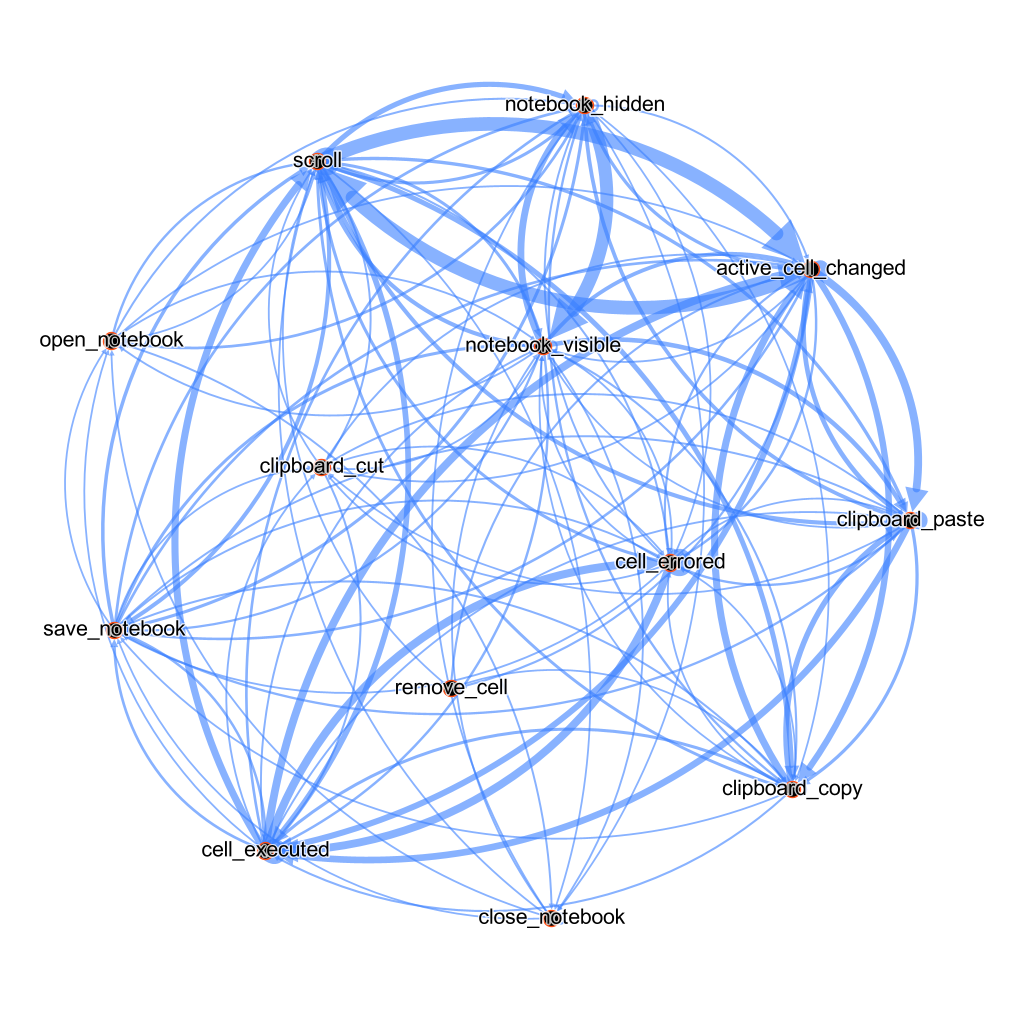

- Social network analysis on patterns of behaviours by individual students

- With new labels for different types of notebooks, I can also investigate how students use different types of notebooks.

In the future…

-

Integrate findings from the telemetry data with reflective data.

-

Interviews and/or surveys for detailed self-report data.

A more comprehensive analysis (work in progress)

This section records all the steps I am taking to analyse the telemetry data. Since this is a work in progress, the contents below may not be consistent. I will try to update as much as I can to have a clear flow. Thanks for your understanding.

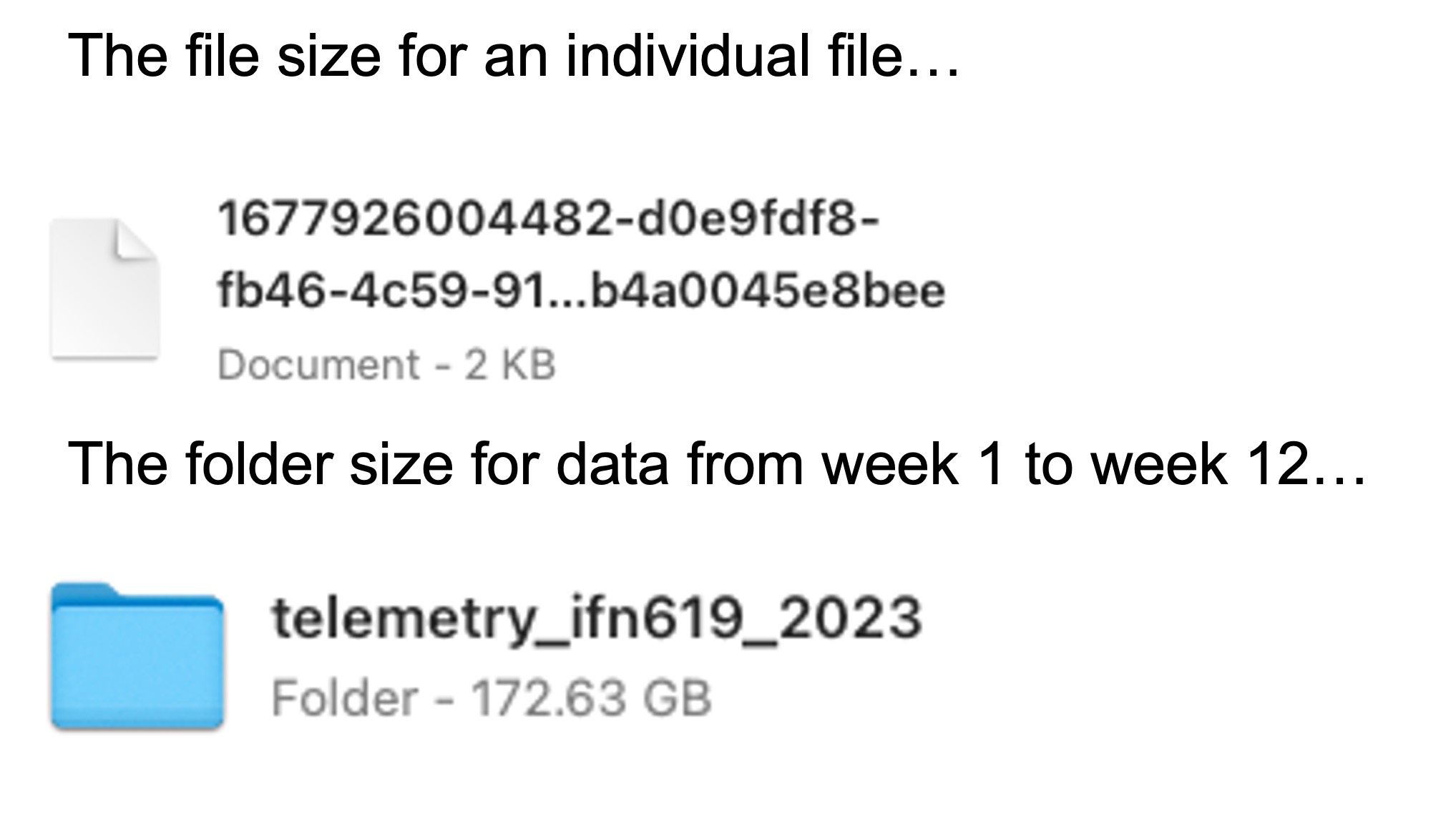

Preparation

I continued to use the code from previous analysis. The first step is to combine all the data into a single file with a tabular format. As mentioned above, one activity (such as a click by a student) is recorded as a single JSON file, including the event and many information associated with the event. Since there are around 7.7 millions of files, it will take a long time to process all the data. However, I only extracted the information I consider to be important to my study at this stage, including event_name, session_id, session_seq, request_time, user_id, error_name, error_value and notebook_name. Below is a short description of those variables:

-

event_name: The name of an event from a student interacting with the Jupyter Notebook. 14 events are recorded in the data:- open_notebook

- close_notebook

- save_notebook

- notebook_visible

- notebook_hidden

- scroll

- cell_executed

- active_cell_changed

- add_cell

- remove_cell

- cell_errored

- clipboard_copy

- clipboard_paste

- clipboard_cut

-

session_id: Every time a student opens a Jupyter Notebook triggers a “session”. If a student opens multiple notebooks in the Jupyter environment, multiple sessions will be generated. -

session_seq: Each event within a session is assigned a session sequence. Since a student can open multiple notebooks, resulting in multiple sessions recorded simultaneously. Therefore, we consider session sequences as a linear process. -

request_time: Timestamp of the event occurred. All the time are UTC time. Later, I will convert the time into Brisbane time to align with the class times. -

user_id: In the raw data,user_idis the QUT student ID. As part of the ethical considerations, I will not useuser_idas the unique identifier. I will replace theuser_idwith randomly generated ID numbers so student identities remain unrevealed. Please note, onlyopen_notebookevent files recordeduser_id, therefore, I have to usesession_idto link all other events to the same user. -

error_name: Events only recorded when an error is occurred in a Jupyter Notebook. -

error_value: The error message displayed when an error is occurred. -

notebook_name: This is the new feature this semester. It records the name of the Jupyter Notebook the event was triggered. Recording the notebook names is important for my project as different types of events may associated with different types of notebooks. For example, for a studio notebook, students may follow the steps of a lecture and fill the gaps as they listen to the lecture; for a tutorial notebook, students will try some code by themselves. Therefore, you would imagine the majority of events for a studio notebook will be executing cells, while a tutorial notebook will have a wider variety of events such as copying, pasting, running into errors, etc. This example is only considering the scenario during a learning experience by a student, it may change when assignments involved.

After over 2 hours, all the raw data have been processed into a single csv file for cleaning and processing.

Data preparation

It is not too bad to reduce the size from the raw data (~250 GB) to the processed csv file (~750 MB). The raw data contains 7,685,002 rows of records. Below are some statistics and initial observations about the raw data:

- Observations on events:

- The most frequent event is

scroll. Top 3 also includes changing active cells and executing cells. This is expected as those three events are the most common activities when a user is using Jupyter Notebook. - The least frequent events are closing notebooks and clipboard cut. This also makes sense, as users tend not to close their notebooks when they finish using the Jupyter environment (but they will remember to save their notebooks). They also tend to use “copy” instead of “cut” when getting information from one location to another.

- More “clipboard paste” events than the combination of “clipboard copy” and “clipboard cut”. More likely students copied information from other resources such as the Internet.

- Lots of errors occurred when using Jupyter notebooks (Top 4!).

- The most frequent event is

- Observations on sequences:

- How long a student stayed within a notebook during a session varied significantly. The average events per session is 537.633, but the standard deviation is 833.919. The median is 243 but the max is 9865.

- The statisitics above doesn’t really mean anything as one person can have multiple sessions simultaneously. In addition, depending on what kind of notebooks, for example, students may spend more time in a session on their assignment notebook, and they might just open one studio notebook to quickly grab some information.

- Events from 194 users are recorded. Please notes the teaching team and administrators are also included in the data. Those data will be removed during the data cleaning process.

- Observations on errors:

- 80 different types of errors occurred in the data. The top 5 errors are:

NameError,SyntaxError,KeyError,ValueErrorandTypeError. All those “popular” errors seem to be quite common in using Jupyter notebooks, particularly for Python beginners. - As mentioned above, errors took place very frequently in the records. Dig into how different students deal with errors might be beneficial to study curiosity.

- 80 different types of errors occurred in the data. The top 5 errors are:

- Observations on notebook names:

- Not surprisingly, most events were generated in the assignment notebooks. Students generated also doubled amount of events in assignment 1 than in assignment 2.

- Students also spent a large amount of time on notebooks generated by themselves (as shown

NaN). - More events were generated in the notebooks from earlier weeks of the semester, indicating students might have tended to spend more time studying in the beginning of a semester. However, since the notebooks from earlier the semester were released early, we also need to consider the length of “availability” to students. So we cannot really make that statement that students spending more time in the beginning of the semester.

- Surprisingly, students tended to spend more time on studio notebooks than tutorial notebooks. The least visited notebooks are the solutions.

Above information may not be accurate because there are lots of issues in the raw data. The next step will be clean the data and some exploratory data analysis as data cleaning progresses.

Data cleaning

Steps as listed below were taken to clean the data:

- As mentioned earlier, only files from

open_notebookevents recorded theuser_id. In addition,open_notebookevents are the first event of each session, therefore, it always shows as 0 in thesession_seq. Each session was automatically assigned asession_id. The first step is to fill thenavalues from theuser_idcolumn based on thesession_idinformation. - Once all the users were identified in the dataset, I then replaced the real IDs with some computer-generated IDs. Therefore, no student identities can be identified from the analysis.

- Since nobody opted out from the experiment, no action was taken to remove any records from the dataset.

- During the semester, a filter was applied to only include the studio notebooks in the analysis. The studio notebooks can be identified by the

notebook_namecolumn. Since the semester for IFN619, semester 1 concluded, this filter does not need to be applied for the analysis. - Note that the student list was from week 3, therefore, if any students who enrolled after week 3 were not included in the analysis (as proposed in the ethics application). In addition, some students might drop out of the unit after week 3. For those students, I will apply a filter to check when was their last activity in the Jupyter environment. No further activities after the census day are considered to be inactive and will not be included in the analysis. There were 193 users in the Jupyter environment, including teaching staff. The next step is to remove inactive students.

- In order to compare dates, I need to convert

request_timecolumn to a datetime data type. I have also convert the datetime to Brisbane time as the originalrequest_timeused UTC time. The new column is named asdatetime_bne. -

Based on the filter, 4 students dropped out of this unit before the census day. 4 students dropped out of this unit after the census day, before the first assignment is due. 1 student dropped out right before the date for “withdraw without an academic panelty”. So the following filter was applied to exclude those students (in the order of the filter):

- Students whose first activity didn’t happen until week 4 (after the census day). Which means those students didn’t use the Jupyter environment until week 4 (or even later). 12 students were excluded.

- Students who didn’t have any activities after withdrawing without academic penalty date. 14 student was excluded.

- Teaching staff members and Jupyter administrator were excluded. 6 staff members were excluded.

In the end, data from a total of 161 students will be included in the analysis.

Other data cleaning steps

Note: this part will be updated as the analysis progresses.

- It’s important to categorise different types of notebook, a new column is added to the dataframe called

notebook_category. The categories are:studio,tutorial,solution,assignmentandself-generated. Please note all the notebooks that are not provided from the unit are considered asself-generated.

Important dates to keep in mind

Important dates for the semester

| Event | Dates |

|---|---|

| Semester 1, 2023 | 2023-02-27 (Monday, Week 1) to 2023-07-04 (Sunday, Week 13) |

| Census day | Friday, 2023-03-24 (Week 4) |

| Mid-semester break | 2023-04-10 (Monday, Week 6) to 2023-04-21 (Friday, Week 7) |

| Withdraw from the unit without academic penalty | 2023-05-05 (Friday, Week 9) |

Important dates for this unit

| Event | Dates |

|---|---|

| No tutorial on week 1 | 2023-02-27 (Monday, Week 1) to 2023-03-03 (Friday, Week 1) |

| Drop-in session on week 4 | 2023-03-20 (Monday, Week 4) to 2023-03-24 (Friday, Week 4) |

| No classes during mid-semester break | 2023-04-10 (Monday, Week 6) to 2023-04-17 (Friday, Week 6) |

| Drop-in session on week 7 | 2023-04-17 (Monday, Week 7) to 2023-04-21 (Friday, Week 7) |

| Assignment 1 due | 2023-04-23 (Sunday, Week 7) |

| Drop-in session on week 12 | 2023-05-22 (Monday, Week 12) to 2023-05-26 (Friday, Week 12) |

| Assignment 2 due | 2023-05-28 (Sunday, Week 12) |

Note: Assignment 2 is the last assignment that requires using Jupyter Notebook for this unit.

Exploratory data analysis

What is the notebook usage like?

At this stage, I am focusing on the class level. The purpose of it is to get a sense of how the data might be distributed. However, in order to find “patterns” of curiosity in the data, I will need to look into individual students’ data. That will be the next step.

Interpretation of the plot above:

- The notebooks were opened by most students are assignment 1, self-generated notebooks, and the first studio notebook.

- The solutions were the least viewed notebooks.

- In general, studio notebooks were opened by more students than the tutorial notebooks.

- Also keep in mind that the notebooks were released at different times. Some notebooks were released towards the end of the semester, so it is less likely to be opened by more students.

- It was interesting to see that solutions were the least visited notebooks. This could be because they received solutions by participating in the studio and tutorial sessions? Or they didn’t bother to look after the sessions?

- Even though the self-generated notebooks can be used as a good indication of students’ curiosity, however, it might not be accurate. Based on some conversations with students, some students used the Jupyter environment to complete assignments from other units. So I will exclude self-generated notebooks from some of the analysis – particularly the ones involving counting the number of notebooks opened by each student.

- In addition to the point above, self-generated notebooks are not one single notebook, instead, it is a collection of notebooks. Therefore, it is reasonable to exclude them from some analysis. However, later when we are looking for relationship between notebooks, it is important to include self-generated notebooks.

It will be useful to know how often each notebook has been used. This can be achieved by counting the number of sessions each notebook has been opened. Again, since the notebooks were released at different times, it is not fair to compare the number of sessions, but it will give some ideas about the usage of each notebook.

Interpretation of the plot above:

- Students spent more time working on Assessment 1 than Assessment 2. However, they might use assessment 1 as a reference for their assessment 2.

- The self-generated notebooks were used the most. This is because ALL other notebooks were generated from the self-generated notebooks.

- Lots of solution notebooks never been opened by some students.

- Module A and Module B were the most frequently used notebooks. This might be because there were released at the beginning of the semester.

- [IDEA] It might be useful to see when a notebook was used the most. A heatmap over time might be useful.

- Since the data were quite skewed – students spent much more time on their assignment notebook. So to emphasise the differences in less frequently used notebooks, I chose to use a logarithmic scale to plot the data.

- The notebooks were organised based on their released dates. A new dataframe was generated that includes the release dates of notebooks. This new dataframe might be helpful for later tasks as well.

Interpretation from the heatmap above:

- The assignment notebooks were used the most, particular when the deadlines were approaching.

- Students might use their first assignment notebooks as a reference for their second assignment.

- Students tended to use studio and tutorial notebooks during completing their assignments.

- Solutions were not used as much as other notebooks. I wonder whether because students already have the answers by attending the studio and tutorial sessions, and only used the solutions when they didn’t record all the information from the sessions. Students uses studio and tutorial notebooks as a reference for their assignments because they might have some extra notes they took during those sessions, which were not included in the solutions.

What about events by notebook?

Now we got some sense of the notebook usage, it will be useful to know what kind of events were triggered by students in each notebook. Again, at this stage, we are still looking at class level trying to get a sense of the data. Based on previous experience, it might not be useful to look at events for all notebooks, so it is better to look at events for each type of notebook.

Interpretation of the plot above:

- The most common event is

scroll, which is expected (except for solution notebooks). - The most surprised event is

cell_erroredfor solution notebooks. Also keep in mind there were the least events for solution notebooks, so more likely there were some outliers in the data. I should check the reason for the high cell error rate for solution notebooks. My initial thought was students might use solution notebooks as their testing ground for their own code. However, the add_cell events were almost non-exist, so it was less likely to be the case. - Copy and paste events were an interesting one. Assessment notebooks had the highest rate for paste among other notebooks, and studio and tutorial notebooks had slightly higher copy rate. There might be a connection that students copy code from studio and tutorial notebooks and paste them into their assessment notebooks.

- The relationship will be easier to see if we use some network analysis to see the relationship between notebooks, and between events.

What about events by students?

Students will have different patterns of using Jupyter notebooks. Therefore, it is important to look at the events by students. The underlying hypothesis: more curious students will exhibit different patterns of behaviour in the telemetry data and moreover those different patterns will correlate with features signifying curiosity. To be more specific, at this stage, I am looking for patterns that signifying information seeking behaviour, which is essentially the backbone(?) of curiosity.

A few thoughts on what to explore on student behaviour:

- How many activities they have in the Jupyter environment?

The more active they are, they more chance that they are seeking information. By counting their activities, we can get a sense of how active they are in the Jupyter environment. Keep in mind some students might use their local Jupyter environment, so the number of activities might not be accurate. However, those students should be able to be identified by their low number of activities and types of events.

- How many sessions they have in the Jupyter environment?

- How long they stay in the Jupyter environment?

Opening each notebook will trigger a new session; each session has a sequence of events; each event has a timestamp. So, we can calculate how long they stayed in the Jupyter environment by looking at the time difference between the first and last event in a session. However, if a student opens multiple notebooks at the same time, the lengths of sessions will overlap; however, we can plot them on a timeline by session to see the overlap. Each student will have one individual plot, so there will be many plots. So it would be better to sample students based on some criteria such as the number of activities.

- What kind of notebooks they use the most?

- What kind of events they trigger the most?

- What kind of errors they run into the most?

Theoratically, different types of notebooks should associate with different types of events, which should associate with their purpose or motivation for learning. For example, students might use studio notebooks to follow the steps of a lecture and fill the gaps as they listen to the lecture; for a tutorial notebook, students will try some code by themselves. Therefore, you would imagine the majority of events for a studio notebook will be executing cells, while a tutorial notebook will have a wider variety of events such as copying, pasting, running into errors, etc. This example is only considering the scenario during a learning experience by a student, it may change when assignments involved. So I also need to consider WHEN those events happened.

- What is their motivation for using the Jupyter environment? (e.g., practice, assignment deadline, etc.?)

Previous questions should build up to answer this question. The challenge here is how to connect this question to curiosity. [TO DO] I might need to revisit the literature on motivation theory and curiosity. And I might also connect this question to the task-oriented learning model.

Below are some plots to answer the questions above.

- How many activities they have in the Jupyter environment?

- How many sessions they have in the Jupyter environment?

A few students had extensively large number of events. Also, a group of students were not active in the environment at all. So we cannot just simply categorise them based on the number of events.

Numbers of sessions tended to be more skewed than the number of events. There should be some positive correlation between the number of events and the number of sessions.

It does show some positive correlation. However, if we look at the right tail, the scatters tended to be more spread out. This indicates that some students who were more active in the environment tended to spend longer time in their notebooks. Below I plot both event count and session count on the same plot, but they are in different scales.

It doesn’t appear that there is a strong correlation between the number of events and the number of sessions, and there are defintely some outliers – very high event counts but low session counts, and vice versa. But keep in mind they are not in the same scale, so it is hard to compare.

NEXT: INDIVIDUAL LEVEL

Next: check each student for event count and session count. use bar plots.

Next: check session length. use timeline.

[TO BE CONTINUED…]

Correlation between events and actual activities

Let’s take a detour here.

The purpose of this part is to match the events with what actual happened during the studio sessions. Ideally, some correlation will be found between the events, and by viewing the synchronised lecture recordings, we can identify some activities that might be associated with curiosity. This is kind of like a comparative analysis, so I am hoping to see different patterns from different groups of students, and I will try to correlate the patterns with curiosity.

Preparation

Here is the rough plan:

- figure out when the studio sessions happened (which week? what day of the week? what time of the day?)

- filter out the events that happened during the studio sessions

- plotting each week’s activity, both group and individual. separate into groups?

- looking for some event intensive activities. for different groups (if exist)?

- looking for some patterns in the events. for different groups (if exist)?

Follow the plan:

- (+step 2) Studio sessions happened in the following weeks: 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11. There were 2 on campus studio sessions and 1 online studio session. All on-campus studio sessions were on Mondays (10am-12pm, 1pm-3pm), online sessions were on Tuesdays 3-5pm. The recordings were only for Monday 10am-12pm sessions and Tuesday 3-5pm sessions. At this stage, I might just focus on the Monday 10am-12pm sessions. The online sessions were in a slightly learning context, so it might not be the same patterns as the on-campus sessions. Later on, I can explore the online sessions a little bit further and looking for some different patterns.

I also included 10 minutes before and after the studio sessions. After filtering, 131689 rows of data were left.

Week 1

32 students attended the studio session. This might not be accurate, some students who didn’t attend the studio session might still use the Jupyter environment. A quarter of the students who had less than 30 events were excluded from the analysis.

Now looking at the real events on week 1. When the activity peaked at 11:46am, it was actually the first time the students were introduced Jupyter notebook. From there, Andrew did a quick demonstration on how to use markdown cells and how to run code cells. But it was the end of the class so he left the practice as homework. Therefore, it might not be too useful to look at the events during the first studio session.

Week 2

By looking at week 2’s data, there were several peaks in intensive activities. I reviewed the video where there were lots of activities, and potentially we can zoom in on those activities.

At 10:33, the first Python task was introduced. Students had around 2 minutes to work on the task. So I am going to look into the activities around 10:32-10:35.

The majority of the events were general use of Jupyter notebooks. Lots of cell_errored events but it was expected as the error was introduced by Andrew. But one student had 89 events while one student had only 4 events.

Students were using all sorts of notebooks during this time. A few created their own notebooks, some were working on the tutorial. A small number of students were using week 1’s notebook and assignment 1 notebook. If I only include the studio notebook they were working on, there were less errors in the data. The numbers of events now ranged from 4 to 52. 2 students were not working on the studio notebook.

From the plot above, I can’t really see any patterns. The only thing that jumped out was cell_execution events. Students who had more events tended to have larger portion of cell_execution events. Apart from some outliers, we can also see there were more explorations for students who had more events.

What I expected to see was students who were more curious would have more exploratory events, as well as executing cells and running into errors. Navigations should be part of the exploring, but it is also part of the general use of Jupyter notebooks. In addition, it is expected to see a reasonable ratio between running into errors and executing cells, indicating there were exploring the code functionality and trying to

Can I really use the number of events as the indicator of curiosity? More events = more active in the environment = more curious?

[IDEA] To look for correlation, instead of counting for how many events, I can look for how many events are associated with their assignment notebooks. Because I can argue that students who spend more time on their assignment are potentially more curious about learning. Then I can categorise them based on the number of events or proportion of events on their assignment notebooks.

Where to go from here?

- This is the beginning of the semester. Since this is an introductory course for stuents who are studying data analytics and data science, we can assume that most students were beginners in Python. The first few weeks were mainly about introducing basic Python concepts and functions and Jupyter notebooks. Therefore, it is expected that some students might not have many “explorations” in the Jupyter environment, because they probably didn’t know what to do.

- The next step is to look at the events throughout the semester, and I am expecting to see more explorations at the semester progressed. So I might need to introduce what was the topic of the week, and what was the task that I am investigating.

- At this stage, I will focus on 3 tasks: from the beginning, middle and end of the semester.

- Summary for what I looked at for week 2: This week was the first week after introducing the Jupyter environment, and it is the first session that students will work on some Python tasks in the Jupyter environment. This task asked students to import a dataset. If students didn’t fill in the gap in the notebook, an error will be triggered. Therefore, it is expected to see some errors in the data.

- Interesting: the students who were active in this task was not active throughout the semester (based on the counts of all events for the whole semester). Only one student from the top 10 of all events showed up in this session (don’t forget there were other two studio sessions).

Week 6

This was half way through the semester. At this stage, students had already been working on mostly structured data and some unstructured data. Therefore, there should be familiar with common data structures and Python functions. The event counts were generally higher (almost doubled) for this week and last week.

This week focused on data visualisation. By looking at the data activity against the recording, there was a peak at 11:23. During that time, the lecturer has already demonstrated code how to improve the visualisation by adding labels and titles. The lecturer asked students to improve a plot by referring back to a code provided earlier in the class. During 11:20-11:24, students were working on the task, and around 11:25, the lecturer started demonstrating the solution.

27 students had some activities during that 10 minute period, however, 21 students engaged with the activities. Interesting thing I found so far is that some students tended to use the class time working on their assignments.

Week 8

This was the final week with some tasks in studio sessions for the semester. The first half of the studio session was mainly demonstrating on term count method for analysing unstructured data. From 11:10am, Andrew introduced a task asking students to follow the similar process from term count to fill in the gaps for TF/IDF. Students had a few minutes from 11:11 to work on this task till 11:16.

16 students had some activities during that 5 minute period, however, 14 students engaged with the activities.

Let’s focus on ALL the tasks in a week - Week 3

[Note: I tried week 5 first but there were only one task was introduced for student to explore.]

The analysis above may not be appropriate because we identified the patterns first and then try to correlate back to the tasks. There might be some cases that a task was introduced but students didn’t engage with the task. Therefore, this section, I am going to review one week’s lecture, and record the times when a task was introduced. Then I will look at the events around those times.

Week 3 was selected as students had been working with the Jupyter environment for a few weeks, therefore, students should be familiar with the environment and basic Python functions. In this case, we can eliminate the possibility that students didn’t engage with the tasks because they didn’t know how to use the Jupyter environment (unless they never attended the previous sessions).

To make it easier to match the actual time with the events, I editted the video to start exactly at 10am, and the timestamps should be easier to match with the recording.

Task 1

- Leading to the task + Explaining the task by the lecturer: 10:23:50

- students working on the task: 10:25:00

- Lecturer started asking questions: 10:26:50

- Lecturer started demonstrating the approach (no coding yet): 10:27:55

- Lecturer started filling the code: 10:29:50

- Lecturer finished filling the code: 10:32:00

- Lecturer ran the cell and explained: 10:33:00 - 10:36:15 (which leads to the next task)

Task 2

- Leading to the task + Explaining the task by the lecturer: 10:37:30

- Students working on the task: 10:38:00

- Lecturer started filling the gap (without talking): 10:38:55

- Lecturer started demonstrating: 10:39:15

Task 3

- Leading to the task: 11:13:15

- Explaining the task by the lecturer: 11:13:55

- Hint provided + solution + asking questions: 11:15:00